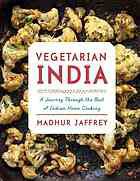

Vegetarian India : a Journey Through the Best of Indian Home Cooking. / Madhur Jaffrey. Published by Alfred Knopf, New York, 2015. 416 pages, with color illustrations, index.

I’d always wondered about how to put together an Indian-themed dinner (or lunch), because generally cookbooks offer recipes for entrees without explanation, as if it were a prerequisite to know where in the menu, and alongside what other dishes, a certain item tastes best! Recipes in Madhur Jaffrey’s Vegetarian India each carry cultural notes plus menu ideas so you are at once familiar with the whole meal in which that recipe might play a staring role.

And yet you can easily choose one recipe by itself, as people say, there are many options from vegetables, grains, legumes and dried beans, to eggs and dairy. (Note that these are actually separate chapters, and unless so named, dairy is not an ingredient in recipes, likewise with eggs.) From the literally thousands of dishes possible for each category, Jaffrey has chosen to highlight ones that are do-able in American kitchens. (See my first attempt at making a spinach dish, Saag Paneer, below!) And the broad range of recipe categories includes soups, vegetables, dals, grains, breads and pancakes, relishes, and drinks, sweets and desserts.

As Jaffrey explains, the term Dal is synonymous with any of the legumes, dried beans, peas and pulses, even familiar chick-pea flour, an ingredient used in so many Indian recipes from soups to desserts.

Among the some 260 recipes in the book are special notes, or cooking tips for the serious Indian-style cook. One of them features stir-fried vegetables which Jaffrey says are known as poryals. These vegetables have the taste of hot, popped mustard seeds and dried red chilis cooked in the pan to prepare the pan for cooking the main part of the dish, the vegetables. Spices are added to the vegetables as they are placed into the wok or frying pan for the final cooking.

Vegetarian India has a strong flavor of the country in its photography, showing cooks and dishes, market scenes, children. Many of the recipes are paired with a colorful photograph of the dish shown in the cooking pan or placed on an individual plate or bowl. The photos are styled to show the food close up, ladled into artisan plates or bowls. Showing the food in an individual setting is a tiny, subtle, but innovative technique to portray the food in the way Westerners view a meal.

Sweets, so delicate and sugary are for the most part eaten separately from a meal, and could possibly be made without so much sugar, or without sugar at all. As Jaffrey describes it, her early childhood was spent in a house on a sugar cane plantation, and sees Jaggery, the raw sugar (not raw as in raw food) sold in Indian and Asian groceries, as a traditional ingredient with an unmistakable and delicious flavor. Likewise the yogurt mixed into many recipes is actually an integral part of the regional cuisine of a part of Northern India called Punjab. One of the dessert recipes, Mangoes Mumtaz (Aam Mumtaz) was so named by Maricel Presilla (“… the most knowledgeable wizard of Latin American cooking…”, page 381) during an interview with Jaffrey. It features fresh mangoes, pureed canned Alfonso mangoes, heavy cream, sugar, pistachios, and a praline of pistachios and cardamom. Wow!

Couldn’t a similar taste be achieved also for vegans, with coconut cream in place of heavy (dairy) cream, and way less sugar—-perhaps a light agave instead of sugar? However, even as Jaffrey recommends some substitutes, the ingredients given in her recipes will lend a true Indian flavor. That’s interesting. Such a cookbook really provides inspiration for many ways of interpreting the recipes—a view actually close to that of Indian cooks, who improvise away any blockage to the desired result.

Recipes have been rendered less than difficult for American kitchens. Each recipe is named with an obvious label for the dish, such as “Savory Whole-Wheat Pancakes”, and the Indian name, Ata Kay Dosay, written beneath. You can choose from 12 recipes for pancakes in the chapter “Grains: Breads, Pancakes, Savories and Noodles”. Pancakes also include the papery-thin crepes called Dosa which require quite a process to make since the batter is fermented for 8 hours prior to cooking. Dosas are a favorite breakfast, snack or lunchtime food, and if you order them in Indian restaurants, you’ll be quite amazed at the array of tastes in one crepe. Dosas are India’s “wraps”, they hold mixtures of potatoes and onions, or chutneys, or tomatoes, cilantro and onions, and many, many other filling possibilities. They’re crispy and perfect for coconut and mint chutneys over the rolled up vegetables inside. Yum-m-m-delicious!

The image, left, shows a Saag Panner I made at home from Jaffrey’s recipe “Spinach with Fresh Indian Cheese” on page 301. Mine has tofu in place of paneer (a home-made Indian cheese). The recipe has lots of ingredients but is actually fairly easy to make. Its concept is to prepare the oil in the pan with mustard seeds and chilis, then spices are added and finally, blended vegetables. There is a fair amount of liquid (not oily) in the finished dish. Spinach, tomatoes, cilantro, and fenugreek leaves are blended together and cooked with garlic and ginger over previously stir-fried onions and spices in a hot pan that was seasoned with mustard seeds and chilis. Jaffrey suggests serving the dish with dal and Indian flatbreads.

Most Indian cooks might have the skill it takes to throw mustard or cumin seeds into a pan glazed with hot oil and roast them to popping stage without burning. For many of the vegetable dishes, following this method prepares your cooking pan by seasoning it well. You can master this technique, too, with a bit of practice! If you can spare a little bit of oil and a few mustard seeds, just to practice, set a frying pan or wok on the stove. Measure out and place a small amount of cooking oil (a teaspoon or less), into the pan and heat it to medium-high. Check that the oil is hot. To do this throw one mustard seed into the pan, and it should sizzle immediately (when it sizzles, then the oil is hot enough). Next quickly measure out a slight ¼ teaspoon of mustard seeds, add them to the pan, watching closely as they sizzle and pop. The pop is key—it means the seed has popped open and will be easily digestible. As soon as this happens, as Jaffrey says, “in a matter of seconds”, as soon as all the seeds have popped, the pan and oil are ready for the vegetables, and when added they’ll cool down the pan considerably.

If you find all of the seeds pop out of the pan!, turn off the heat, but also place a cover or lid over the pan, so you won’t loose all of the seeds onto the floor and everywhere else! Also note that this means your pan is too hot! So stop, wipe out the pan, let it cool a few minutes. Then try again with a bit less heat.

Dosa, Paneer, Chapatis, Upma, Biryani, Dal—these Indian names of dishes are found in the menus of most Indian restaurants in the U.S., so we are a bit familiar with them on site if not by taste. Vegetarian India‘s recipes have been interpreted for American kitchens, but I would not say that they are easy. But with a little cooking practice, you can easily create Indian-style entrees.

The regional cuisines of India are original and unique, state to state, if not village to village, even house to house, in a country which Jaffrey describes as the size of Europe. It’s mind-boggling to behold and perceive of the variety of dishes available to the serious food-writer, so many of which are translated in Vegetarian India for adventurous cooks. There are hidden gems in Vegetarian India, the kinds of tips and recipe ideas that will place your cooking repertoire at the next level of fun and culinary expertise.

Follow